SIMPLE – FASTER – CAPABLE

SIMPLE – FASTER – CAPABLE

One of the major influences in my martial life was Ray Medina. One of my best friends Roger White and brother cop (patrol and detectives), and Roger introduced me to Ray in 1986 because he knew my personal frustrations with classic martial arts, dating back to 1972.

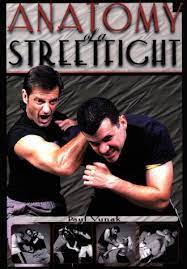

Ray was already a karate-kickboxing champion fighter in our region but he’d discovered the Bruce Lee world, Dan Inosanto and Paul Vunak. Jeet June Do and Filipino martial arts, Thai, Shoot, Silat and that unique street fighting that Vunak pioneered in the 1980s. Ray was traveling back and forth to then the “Mecca” – Los Angeles for all this. And was addicted to seminars.

I “hired” Ray to teach me and basically several days a week for years we’d meet. At this point money was no object. Addiction is addiction. We’d meet up and I’d ask, “What are we doing today, Ray?” And it took a while to figure it out but basically we did what HE needed to work on, not me, which meant him beating me up quite a bit, under the guise of teaching me. BUT…I learned a lot. You can still learn a lot that way and of course I got to experiment on him too. I recall that Inosanto said that he did this with Bruce Lee, and Lee would wind up beating Dan up a lot. “Basically I was Bruce’s punching bag,” Inosanto said once.

Ray and I started hosting the big names in our city. I began attending seminars with him and I quickly learned that we were both interested in visiting systems and arts, but only to learn how to beat them. We were like spies in ememy camps. Many if not most seminar (and class) attendees attend to learn those arts, embrace them, get rank, to eventually teach them. Early on I learned that our spy motive was to learn how to beat what every one else was doing, not replicate it, join it, or worship it.

True, we were both card-carrying martial addicts, but for Ray he was spying because of the fighter in him. For me, I was spying because I had to arrest people. So, we would study material with the sole purpose of beating it. Inadvertantly, we did learn other systems and arts but sort of, from this ass-backwards, spy way.

Ray eventually died of a stomach cancer. Through the years he knocked me out several times when kickboxing, but he also knocked some sense into me which was worth more that those occasional, nausea-LSD-like, TKO dreams and the occasional vomiting.

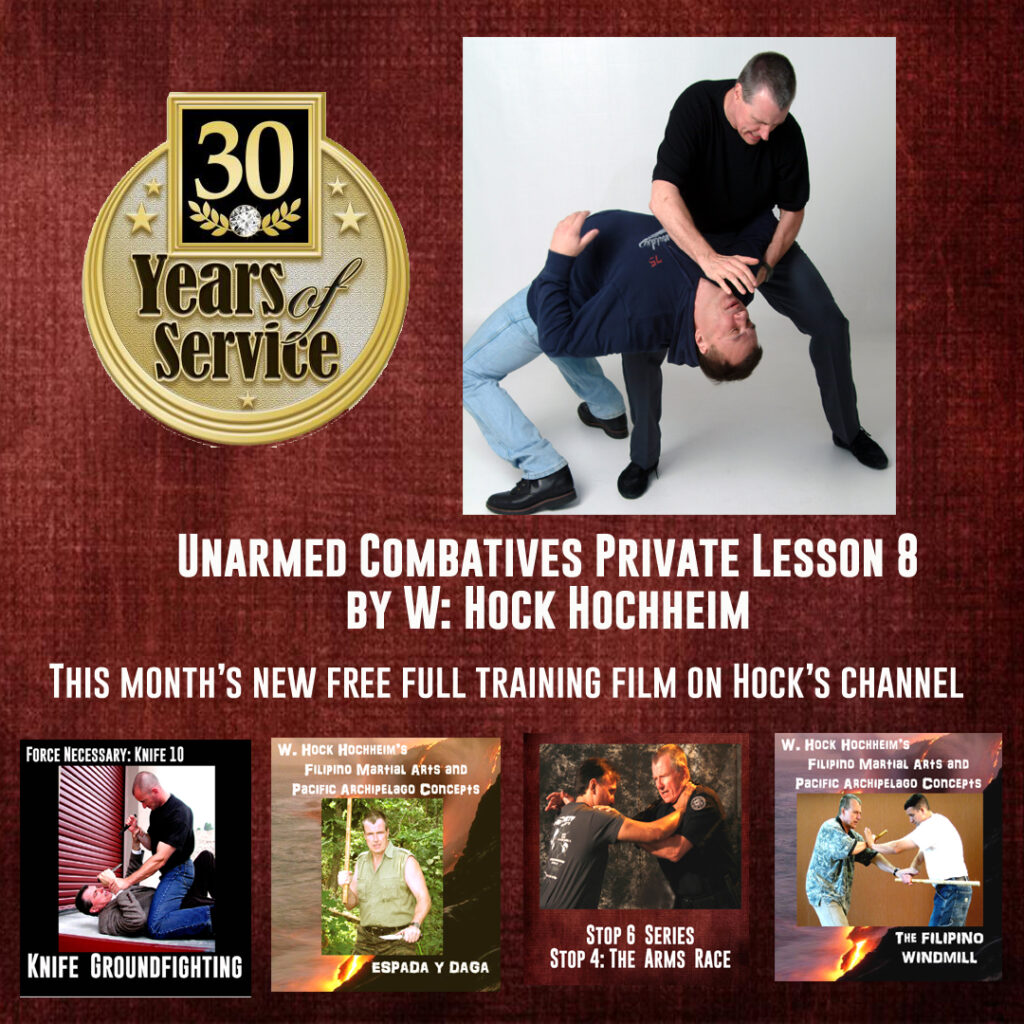

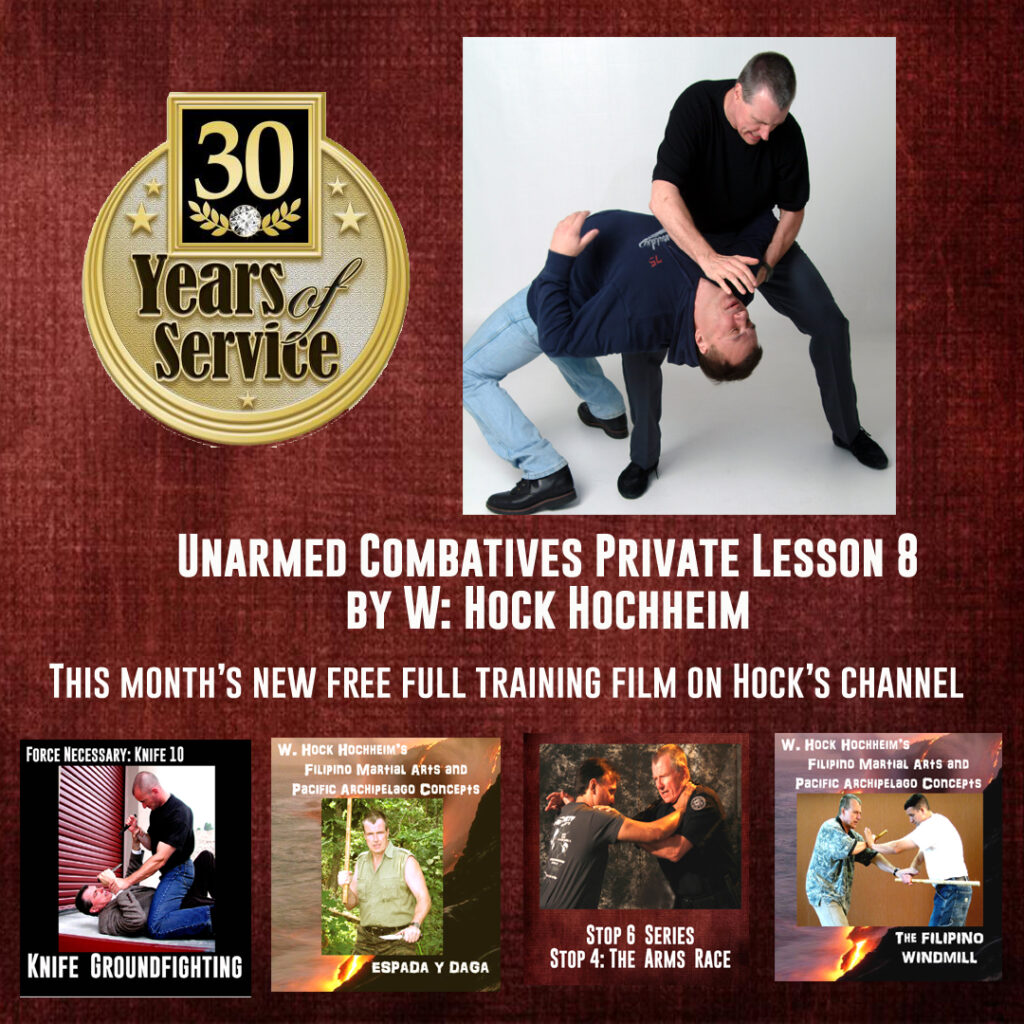

Check out all of Hock’s free training films on his TV channel, click here

Kajukenbo Okayama: Hoch, tell us about yourself.

Hock Hochheim: Well, that’s sort of the “Who, when, what, where, why” that I use everywhere. And I do ask that question…“Who?” “Who are you, really?” And in our business, who do you really expect to fight? There’s a psychology where older people think less of themselves, and then younger people think more of themselves, in terms of what they think they can do, and who they can fight and win against. This is so true that there are actual psychological terms for both of those categories, but they escape me now. I have to continually look them up every couple of years to remind myself.

But I’m just a former army, military, police investigator. Then Texas police, and in most of that time, in those 23 years, a detective, about 16 or 17 years of that. And since 1972, starting out at Ed Parker Kenpo-Karate, I’ve been a martial artist, other than a few rare years maybe, while in the army. I’ve just done this every day for…I think the number now is pretty much 50 years, 51 years… Fifty years, fifty-one years of thinking about/worrying about/being psychologically obsessed with these elements of fighting. To a fault, I think. I think it’s a bit of a mental sickness.

KO: (Laughing)

HH: I should be thinking about other things. Which I do, yes. I think about writing my novels, but also my mind wanders back to organizing this martial material…what’s better, what we can cut out, what we absolutely need. And in the terms of hand, stick, knife, gun, war and crime, it’s quite a challenge. It’s still a daily challenge, after all these years.

KO: Tell us more about your martial arts history.

HH: I was in Kenpo-Karate, I guess about a year, and then I went to the army. So, I had this established impression of martial arts. In the army, there was just a couple opportunities to train. Boxing. Police Judo. First of all, I was in Korea, and I wasted my time there, martial arts speaking. I say I wasted my martial arts time there because…I hate to use the word “brainwashed”…but I was so immersed in the idealism of parker Kenpo, and how superior it was, as they told us, that I really did not want do anything else. Now, I should have done Hapkido at least while I was in Korea. I’m not really a big fan of Tae Kwon Do, I like their power kicks, but gosh, I could have done Hapkido! We had opportunities. There were a couple ROK Marines there teaching military combatives classes at another base gym, So I did that.

The military police academy was kind of big on boxing as a support system, which also had its inherent problems. But since I was in Karate, as soon as I got there, I did their boxing stuff. And it’s very hard to take sports boxing with gloves and transform it into bareknuckle fighting and reality arrests. There’re real problems with trying to make those two come together.

And so, anyway, then I got out of the Army, I did Karate and Jiu-jitsu back in Texas…the stand-up, old school Jiu-jitsu. And then, in 1986, I started in with the Jeet Kune Do people. And that was just a big mind explosion. I was very happy to get out of the classical framework, as suggested by Bruce Lee.

So, we’re talking Dan Inosanto and his top instructors. Thai boxing, the Filipino martial arts, Jeet Kune Do, Wing Chun…all the things that they were doing was just a massive amount of cool investigative stuff. And that went on, probably, I guess, until about 1997. Oh, and then of course I picked up with Ernesto and Remy Presas. And that was a huge chunk of time. I got very close to both brothers. They often stayed at my house, which was a fantastic opportunity for me.

I lived in middle of the country, and they needed to stay weekdays somewhere between their weekend seminars, and I was a bachelor, and they just flat out asked me: “Hock, can I stay, you know, Tuesday through Thursday?” Or, “Monday through Friday morning?”

Then about ’97 I really decided to get free of everything, and clear my head, and create exactly what I dreamed of. Y’know, all these decades, I was in the pursuit of the “perfect martial art,” so to speak. Survival fighting with hand, stick, knife and gun in crime and war, standing through the ground. And after I’d done all of these things, I realized there was none. No one perfect thing.

And so I decided to embark on this blend…I guess the best word is “combatives.” A word that wasn’t popular in the ’90s, but I picked that word anyway. It became popular later, to a shaky extent.

KO: Before you got into Jeet Kune Do, I hear you had a run in with Kajukenbo?

HH: Yeah. So, in Ed Parker Kenpo Karate, North Central Texas…which was one of the rarest of official martial arts schools you’re gonna find back in the late 1960s and early 70s. I found one and joined. We had two private lessons a week, and Saturdays was set aside for a group lesson. A couple of hours, and that was your typical group martial arts class in many ways. And at the end of the Saturday session, they had organized…Keith See was the guy, one of the first generation Parker guys…they had organized a sort of open, sparring class with as many other schools as you could find at the time. There was Tae Kwon Do, there was Kung Fu, there were various arts. And since part of Parker Kenpo was very kickboxing oriented, we usually sort of “won-beat” everything against these other people.

It just created a “wow” factor, like some of these folks were really dramatically moving into artsy, unsafe positions (as taught by their arts), and we’re just kickboxing at this point. Not good for them. We were always very friendly. There weren’t any kind of feud problems.

But then all of a sudden, who shows up one of these Saturdays in 1972, but the local, Kajukenbo guys. And all of a sudden, they were like us. They were a mixed kickboxing outfit. And so “Wow!” we said. And so no, we did not overcome them. And y’know, it was very much an equal experience. “These guys are like us! They’re from Hawaii, they’re doing the same things…” So that was my first introduction to Kajukenbo, and these guys. And, as time marches on, we’re all going to seminars, and we get to know each other and stuff. And then of course a long time ago, early 1990s I met Dean Goldade, he was a Professor Gaylord black belt. We worked consistently together for decades. I also got close with another Prof Gaylord guy, great guy, Ron Esteller. I have done dozens of seminars at his place over the years. I’ve done a seminar with Prof. Gaylord in California, so I know all these guys, and it’s just been a gigantic friendship ever since.

KO: What was it like in the martial arts world when you first started?

HH: Those guys were super tough. I joined…I started, in 1972, just after the blood and guts era of Karate training. It was sort of an assumption that this old martial arts training style could not be a successful business, if you have to vomit or bleed every Tuesday

I saw the same thing happen to Thai boxing. In, oh I guess about, the late ’80s or early ’90s, where suddenly you were not beating the snot out of each other all the time in class. Before that there were just constant injuries, and business problems with that. And of course Bruce Lee had this same problem at his YMCA classes in Los Angeles, which is why he created that YMCA boxing program, which Tim Tackett taught me. There’s a lot of great, hardcore, application drills in that program. It meant that James Coburn didn’t have a black eye when he went to the movie set. And the doctors and the lawyers training with Bruce, y’know, weren’t all busted up.

So, he created this kind of program that was focus-mitt oriented…and you’ve seen bits and pieces of it in the Jeet Kune Do world through time. The little sets of things, strike/counter-strike, sets of three, sets of four…I still use those. But my mission is not to create a boxer or a kickboxer. My mission is to create a bare-knuckle, self-defense endeavor. So, I still use a lot of that Bruce Lee YMCA program.

KO: Tell us more about that program.

HH: Well, everything is called “Force Necessary”. It’s based on using only that force necessary to win and survive. The definition of “winning” is different situationally and personally. I have a couple of rules about what a fight is. “Checkers, not chess” is a motto of ours, and defining what you don’t do, helps you define what you do do. Defining what you don’t wanna’ do helps you define what you wanna’ do.

Is a fight “chess” or is it “checkers”? I believe a real fight under stress is checkers for almost all people. I mean, look at the limited list of techniques you see in the UFC. So I have an internal meter in my head that can spot the chess applications. Einstein said, “Keep it simple but not too simple.” But the definition of simplicity changes with people. So, if you have a super talented martial artist, you should remember that their definition of simple, or “checkers,” is higher than the average person.

Trying to keep things simple and as realistic as possible, in the hand, stick, knife, gun realm, that is really core, essential stuff.

I am not going to create champion kickboxers. Or champion MMA people. Or champion BJJ people. And in actuality, a lot of those people that do advertise they create those champions…they don’t really create champions anyway. Y’know, they just have a program, and they do the best they can with it.

My goal is to create self defense people. And again, there’s of course that large middle realm of “normal” people. But then of course if you have a special athlete in there, you have to make sure you hit their level of simplicity, which is higher.

I can look at people and just decide what they need to work on. For example, here’s one example, I’ve tried to look into the subject matter of the density and size of fists. You can look at a person and say “You shouldn’t be punching people, because look at how tiny your fists are. Switch to palm strikes.” And then I have another friend who’s got fists like cinder blocks. And he needs to be punching everybody.

I just ran across this in Hungary last week, in Budapest. A kid wants to pursue all this information. And I can look at him and say “You need to take a couple studies of, like, how Bruce Lee moved. Because you’re small, you’re thin…ya’ know, you look like him. What’s your arm length?” Etc. “But you, Mr. Tank standing next to the kid, at 280 pounds, you should develop your own “bruiser” approach to this.

I can tell you many great stories. I mean, Dan Inosanto said in a seminar once, decades ago…and he was a high school football running back champion…he was getting the ball, and crashing into the line…and his coach said “Dan, why are you running into people all the time?”

So, he named somebody famous, but it was a giant running back…and Dan said “Well, I’m trying to be like my hero ‘Joe Blow’ (whatever his name was). And the coach says “Dan, Joe Blow is 6’4. You’re 5’ 7”. Pick…another…hero.”

And that’s a great piece of advice for people, so I try to keep everything in this system essentially “core” simple, and in the end it’s up to me and the people to make their own thing that works for them. And not try to pretend to be somebody else they can’t be. It’s the “who” question again. “Who are you, really?”

And then of course you come around to the subject matter of instructors. As an instructor, despite your shape and size or shape, an instructor must know everything. Because he or she is now in front of all shapes and sizes, and ages, and strengths. So there’s the question, is your guy, the attendee, someone who wants to defend themselves, or do they also someday want to be an instructor? Well, the instructor has to learn everything. Two-fold responsibility.

KO: Tell us more about your view on teaching punching in your system.

HH: Well, punching is cavalierly taught in martial arts without any warnings. The big problem is the “bicycle helmet” area of the head. That’s the real hand breaker. Because the jaw gives, the neck kinda’ gives, and you have some chance of surviving that without injury. But when the bad guy reflexively lowers his head…you’re aiming for the nose, you instead hit the bicycle helmet part of the skull…you’ve got a broken hand. Or say, versus a hook punch, they turn their head sideways and down, and you got the split knuckles break.

So that’s why punching is level 5 in our empty hand module, of the 9 training levels, because I think it’s taught way too cavalierly in almost all martial arts. I mean, in those schools you’re punching on day 1 and no one is telling you this could be bad for your hand and how to avoid problems. What about a palm strike instead?

I’m a puncher from day one, and my hands are not that small. And I’ve only had two real problems and one surgery, with a hairline fractured bone because of an uppercut to a jaw.

KO: How does knife/gun/stick fit into the world of martial arts?

HH: Well, I guess it doesn’t in unarmed systems. But it should. It has been connected, if you think back to the samurai. They were shooting guns at each other eventually. Because the human race, psychologically, has been built to kill from a distance. This has been proven and proven and discussed forever. Archery was the big deal way back when, and then guns. And it’s just harder, face to face close, to kill a person. Just, psychologically.

So, today, there are a lot of guns. I don’t teach marksmanship at all. I have interactive/simulated ammo shooting training. In situations. That’s all I teach.

And of course the real challenge is to shoot cold, meaning that you are suddenly attacked…at that point, what is your skill level shooting cold instead of your skill level on the fourth set-round, warmed up on the range…and they say even psychologically, preparing yourself to drive to the range…getting everything ready to go, driving there, entering the place…all results in you not being all that “cold”. All of that is starting to prep you to shoot. Warming you up. Instead of being ambushed. And being ambushed is the greatest trick of all to pull off.

So I try to have situations that are based on reality. And I have very safe, fake guns, and very safe ammo, and we are able to work through many repetitions of realistic problems. You’re not learning gun combatives unless moving, thinking people are shooting back at you. It’s just that simple.

Of course, this approach has been accepted now, by the military and policing, and some smart civilian courses. I started to do this in the 1990s, and people were hesitant about it, thinking the only solution was – “I just need to draw faster” and stuff, and now as time has marched on, anybody with any sense is exploring interactive shooting with simulated rounds.

And of course, everyone’s been fighting with some kind of impact weapon or sword, but I don’t know if these things are officially, classically, “martial arts”.

KO: How did being a police officer connect with all your training?

HH: Well, for one thing, I didn’t shoot a lot of people. Cause I could fight ’em. That was a big deal. There were circumstances where I could have easily, legally, shot somebody, and I knew I didn’t have to. And so, I didn’t. And that’s from all this training and realistic confidence. Of course, that was not popular at the police department, because it set a new standard for these other people.

I do know from the reaction of people that that was kind of a problem. I’d bring a guy in, handcuffed, that I could have shot, and some old timer would be at the police department smoking a cigarette…and he’d say “Why didn’t you just shoot that son of a bitch…?”

And I would simply say “I didn’t have to. I didn’t have to shoot him”.

So that was the biggest thing. My days, the ’70s, the ’80s, and the ’90s,…basically speaking, if you were toe-to-toe, face-to-face with a guy, and a fight really started, we would basically, legally, try to beat the shit out of them until he quit resisting. You can’t do that anymore.

Because here’s the deal…if you arrest someone and wrestle with them…which is extremely dangerous, especially on the ground…and you get them in a “submissions/tap out” hold…they’re not gonna’ tap out, because in most cases they don’t know how to tap out. But you’ve captured them. Because I’m telling you, when you let the guy go, he continues to fight. Or he runs away.

So the goal of submission wrestling in arresting people is really not good. Now, if two or three people show up…your partners…you can try to work that out…and it’s usually still an uncoordinated mess.

And I’m a big fan of catch wrestling. Because as a martialist, we must know everything about the body. And we must know every joint, which way they bend, and which way they don’t bend. It’s our responsibility to know that. That doesn’t mean I have to become a brainwashed wrestler. Judo people forget to punch. If you’re in a system that doesn’t have a complete, competent doctrine, huge chunks are out. And if you exist in that system for too long, you forget many important things.

The old school fighting ways were: you hit the guy, stun the guy, throw him down. And handcuff him. That simple formula did help me tremendously in policework.

Nowadays, it’s a whole different animal.

KO: How about the stick part of your program?

HH: I approach the knife, the gun, the stick, and the empty hand in the same way. In stick training though, if you remove the Filipino stick vs. stick fighting, there’s not a whole lot left to the stick study. A regular person is not going to be fighting with a 28 inch stick by happenstance. By happenstance, you’re standing on a street corner with a 28 inch stick, and you get into a problem with another guy who has a 28 inch stick? Not likely. At the stick versus stick part, that point the stick fighting becomes more of an art, more of a fun, abstract study, a hobby, and a martial art.

If you remove stick vs. stick fighting from the program, there’s not a whole lot of material. So, I work on that for the Force Necessary Impact Weapon: Stick course, we worry about self-defense survival. A little dueling, yes, but not at all like a Filipino course.

KO: And yet you seem to have a strong interest in the stick.

HH: Well, I started with the Inosanto world in 1986. Like so many people, Dan Inosanto changed my life. With the things that he was doing, and the people that he had. I spent a lot of time with Terry Gibson in Tulsa, Oklahoma, who Inosanto said was one of his top five people. I hosted Terry, I went to his house, I went to the seminars they did up there. I met Paul Vunak, Larry Hartsell, all through Terry Gibson. But part of the whole thing with Arnis is the overabundance of stick work, of single stick work.

As Ernesto Presas would explain, you really have five areas of so-called “play” in Filipino martial arts. There’s

So, sticks appear in three of those. Just naturally there’s an overabundance of it. Espada y daga is “sword” and daga, but it’s become “stick”, mostly. Some people justifiably call it “stick and knife”.

I myself am not particularly obsessed with sticks, ya ’know. I just have a long accumulated knowledge of stick stuff. And I have a world where customers want to see “stick” stuff. They are magically so interested in it. So, I am happy to do stick material, and it’s kind of fun and so on, but it’s not my main interest or thing to do.

And I’m amazed…I see these people that have weekend seminars, three-day seminars…single stick, seven hours each day. Wow! And they’re just hypnotized, and mesmerized, by stick versus stick. These people really love it.

And as a result of that, I am happy to do stick stuff. And frankly, I do know a lot about it. And Filipino martial. I’ve had lots of exposure, time and grade. Dan Inosanto, at first he was doing Pekiti Tirsia, and then he switched over to Lameco…and in the meantime, he’s still telling you what Johnny Lacoste did, what Serada does, and Illustrisimo…

I was exposed to all these different systems, and I started going to all these others with an open mind. I started going to Remy Presas seminars. Remy was charismatic, he was the real deal…he fought in the Philippines, and had killed people, in stick challenges, that’s not very well known, but I’ve written about it on my pages. So, I was going seminar to seminar. I was just a seminar attendee to him. And then some guy calls me over and says “Do you know about his brother, Ernesto?”

I said, “Never heard of him.”

And so, he said “Well, come back here behind this curtain.” And we started to do Ernesto material, and then I started to do Ernesto material for four years. As well as all the Inosanto material. As well as Remy material.

Then I get a phone call from my guy, and he says “I’m going to the Philippines for a month. You gotta go with me.” So, I’m thinking, I have hundreds of hours of comp time saved up as a detective. And you have to take that time after a while. So I said, “I’m in.” I’m a bachelor, I sold my car, we went. And there was only like 7 or 8 of us that went. It was great. Negros Island and in Manila.

The next thing you know, after about training in the Ernesto system for five years…on the last day, a black belt test and I get this black belt “guru” title, there in Manila. I come back with this lineage and an actual list of system requirements to do that was really elusive with other FMA instructors. Most people just had to spend a whole lot of time (and money) with “Tuhon Joe Jones” and maybe…maybe…you’d get something. I had a list and a lineage line straight to Manila. I said “You do these ten things, and you can get this belt ranking from the Philippines.”

“WHAT?!” they’d say, “You mean these ten things?”

Yeah! I said “I can do that for ya. And if you do these 25 things, you can be a basic instructor, as granted by Ernesto Presas in the Philippines.”

“WHAT?!”

So I started to become popular because I was, I had this connection. Back then, everybody wanted a backyard workout, a garage workout. Some guys rented a space. But everyone had a dream that was financially hard to do as time marches on. And that’s really how I became so-called “famous.” I started touring all over, people started asking me to these 10 things, to do these 12 things.

Meanwhile, I’m still with Remy Presas. Again, at those early times I was just another seminar attendee to Remy Presas, and Remy finds out I’ve been to his house on the Negros Island, that I’m working out in the Philippines, he contacts me. Then he and I became close. He knew I cared that much to do all those things. I hosted him numerous times and he stayed at my house a lot.

Both brothers had similar systems, but they’re different. Ernesto’s is much bigger. Ernesto was obsessed with making the perfect Filipino system, in those five areas of play. And as a result of that, he was tortured, and he never could complete it. He was constantly changing it, constantly messing around with it. Whereas Remy just wanted to do enough so that you could fight well, basically.

Both these guys were Karate black belts, they’re Judo black belts, they spent their entire lives doing martial arts. So. they were very well versed. They could fight anywhere, with anything.

But, back on the stick subject, as time marches on, the obsession with single stick with people is amazing.

So that is my…not a love/hate, but a love/infatuation with sticks.

KO: You’ve written quite a few books, right?

HH: Well, I have a very popular knife combatives book…

KO: (Thumbs up. I love that book.)

HH: …It’s got about 1,400 “how-to” photos. It’s very popular, it sells regularly, and now it’s an e-book.

Then I have an impact weapon book, which is not based on Filipino stick. But it is the blocking, striking, and grappling with an expandable baton, or any type of impact weapon that you have. I’m in the middle of making an unarmed combatives book, which is gonna be another heartbreaker to make…2,000-plus photographs, as much of my knowledge on the subject as possible I can record.

Then I have to do a Force Necessary: Gun” combatives book, which is nothing but all the sims ammo, interactive scenarios that I teach.

Those are the “big four”. The idea of writing a Filipino martial arts books is just overwhelming. I get a kick out of seeing these guys who write a “Filipino Martial Arts Book”, and it’s like a 128 page book. No (laughing), it’s gotta be as big as a damn spaceship manual. Now, I could do a five books on the five areas of play, that is digestible, possible. But y’know, I’m 70, I don’t know if I’ll get to finish ’em. And then of course, I do write novels, and I have a western series, and I have a detective series, and those take up a lot of my time.

KO: With modern technology, how important are books to the modern martial artist?

HH: Well, I guess that videos are superior, because you get to see what’s happening, but historically books are still important. They used to claim there were five ways to learn something, visually, reading, doing, etc. I don’t remember the others…but I’ve forgotten them because other experts have come up with five or more, better, ways to teach and learn. The original “five ways” is kind of an old school mythology that fell out of favor. I do know that you have to have different routes to people’s brains to teach them.

So, videos are pretty important. Sometimes I wish I had a GoPro I could plant, real thin, right between my eyes, and do what I’m doing and show people my (their) point of view, our perspective. And that would be another important way to learn.

But, for many, one of the main methods of learning is a book. And that’s why when I do these combat scenarios in books, I try to do each important step in the photos.

I’ve made about 45 training films. But with the demise of training films and the shortening attention span versions of films you see on YouTube…pretty much, the one-hour training video has lost the ability to be sold. Like Paladin, once a big international martial arts video company has collapsed. Century has bought the Panther videos but they don’t seem to be selling them. Nowadays, if you have an itch to learn…say…wrist locks, you type it in, you watch 17, three-minute YouTube videos on wristlocks, and you are sated. You’re not gonna’ buy a $40 wrist lock video. So, that is the problem with bothering to make movies anymore.

Of the 45 movies I’ve made, many are now free on my YouTube channel. I’ve decided once a month, I’m gonna put a 50-minute to 1 hour video up for free on my YouTube channel. Because of how things are changing. I don’t want the videos to sit and rot. If I was rich, I’d do all this for free anyway. That way at least people can watch and learn something.

KO: Are there any martial artists/martialists/fighters that you look/looked up to?

HH: Well, y’know, I really like Bas Rutten. I wish I could spend about year with that guy. But there are others that are competent fighters. I know that Bas will tend to lean toward the MMA/combatives thing, but he’s a pretty smart guy. Eric Paulson is amazing, the JKD guy. He’s amazing. He doesn’t seem to be hypnotized into wrestling. He knows the big picture. The information in the big picture is constantly on the tip of his tongue. You can always ask him “What about this? What about that?”

Gosh, and through the years, there’s been so many, but in particular categories. Scott Reitz. A founding member of LAPD SWAT…there’s your gun guy right there. Paul Howe, former Delta Force, gun guy, teaching in Nacogdoches, Texas. I guess I tend to lean towards extremely experienced people.

And then, some of the smartest people in the martial arts that you will ever meet, will run a quiet little school in a strip mall, in “Bumscrew”, Wisconsin. And nobody knows about them, but they’re brilliant people. And that’s just the way that it goes.

KO: What are your hopes for fight training, combatives, martial arts, etc. in the future?

HH: The bottom line is that I hope that everyone will be happy doing what they’re doing. Because much of it is a sport or a hobby.

The only thing that I ask for, that I ask and dream of, is that everybody who’s doing their hobbies and sports realize where it fits in survival. How does it fit in? Does it fit in? That’s one of the “who, when, what, where, why, and how” questions.

You have to have a martial IQ. The intelligence quota, to select the right things, and keep improving. If you wanna wrestle the rest of your life, and you still realize that this isn’t the cure for all fighting, and realize you don’t have a stick/gun/knife involved in this, and notice if you have forgotten how to punch and kick, “I just know this wrestling thing, and I love it! Maybe I will do a sports tournament thing someday, wouldn’t that be fun…”

Yeah. Go. Have a blast. Just know where everything fits or doesn’t fit. In the end, I want everybody to be happy with what they’re doing. They’re off the couch, they’re exercising, they’re part of the social aspects of a good school…you have Christmas parties, get togethers, you have kinship…all these great things can happen because of a martial art class, or a combatives class, or whatever. Just have an idea, from someone, somewhere, where your art fits in real life. And then, I’m happy. If you’re happy, I’m happy.

KO: Do you have any advice for martialists or Kajukenbo people in general?

HH: Well, Kajukenbo is, to me, a wide-open system of learning. They want you to exist in those categories and keep evolving and learning. And that to me is the best advice. Keep evolving and learning.

Hawaii was an amazing place, and a transition for so much.I remember Ed Parker saying that he tried to take all the Karate and Kenpo and turn it into an art for a bigger person. To Americanize it, so to speak. I think Kajukenbo did that too. And now it’s one of those martial arts that’s all over the world.

Back then there wasn’t a lot going on. And the arts there in Hawaii were the established beginnings of things. So, it doesn’t surprise me that a lot of guys were in those two arts (Kenpo and Kajukenbo). Nowadays, the popularity to me seems to be with BJJ and Krav Maga. You don’t see the Kung Fu school so often anymore.

To read more interviews like this, be sure to check out Kajukenbo Okayama’s recent book, “Blood, Sweat, and Bone: The Kajukenbo Philosophy.

https://www.amazon.com/stores/John–Hojlo

MMA – Mixed Martial Arts? Or MMA – Mixed-up Martial Arts?

The tabulators tell me that 2021 this will be my 51st year doing martial arts – having started in Parker Kenpo in late 1972. I’ve always

From the 70s on I was working out with what was available, old school jujitsu, boxing, karate, police judo-defensive-tactics. Then in 1986 I starting with the Inosanto Family systems (Thai-JKD-Silat-FMA-Shoot fighting) and Presas Arnis. In 1990 I started Aiki-Jujitsu with a professor in Oklahoma. I guess I was spinning a whole lot of plates? But on some level, despite the differing outfits, patches and the nomenclatures, many times I noted I was often doing the same basic, good moves in different systems, despite the change of systems with a tweak here and there. Sort of a name-game change.

Makes me think of the Bogey movie song, “You must remember this, a kiss is just a kiss, a sigh is…” But you really must remember that a

I see my martial life that same 1, 2, 3 stages way that Mr. Qingyuan suggests, which leads me to my mixed-up-martial arts phrase and phase. Bear with me. You might see yourself in this dharma-dilemma-development?

For quite some time I played a name-game switcheroo. I changed clothes and mindset with various martial art class scheduling. Often in the same night! I can best describe this with two quick stories.

Each of the classes definitely had a different mission, feel and goals. I’d got the vague idea back then that these things could be blended, especially via the Bruce Lee ideology I was trying to grasp,

By the way, this division of subjects is a martial arts school business model. More classes. More themes. More students. More outfits. More testing. More money. Nothing wrong with that – just saying. With many other instructors and schools in this business model, we studied to become one system-artist when doing that one system-art. MMA, the evolved business model became closed studies to learn different things – yes – but, inadvertently, keep them separate. Divided. Which, whether I fully realized it at the time, was NOT what I wanted, but I wasn’t quite “martial-mature” enough to realize it. I had no “eye” for it. (More on “eyes” later…)

I used the Who, What, When, Where, How and Why questions.

While turning the all-mixed-up to the mixed-blended, I have a lot of teaching stories for each “W and H” question from these last 26 years, the second half of the 50. I believe these to be informational, entertaining and educational stories, but book-length, and not good here for a short blog.

It should come as no surprise that in the big training picture, modern MMA (as in a blended “UFC style” With ground n’ pound, and I repeat WITH ground n’ pound), Combatives or Krav Maga formats evolved to fill in that anxious, wandering market place of folks like my early self, seeking the stripped-down blend, the best mix. It’s just business and filling the gaps. “Nature abhors a vacuum,” as they say.

Something much bigger is going on though. In the history of mankind, its overall DNA, a small group of people – us – struggle to keep fighting skills perpetuating, alive, for the drastic times that come and go, and keep us all alive. This genetic drive manifests in many different ways, like karate or combatives. It’s that big picture, so big we don’t see it, down to the smallest of pictures. You. You and the quizzical questions and choices in your head. Why do you do this stuff? Well, I just gave you one big DNA reason you might not have thought of. For some of us? It’s our inherent duty to mankind. We are the odd, weird ones, keeping this alive.

I certainly don’t regret all the mixed-up, past exposure, the blood, sweat and cussing since 1972, even though I wanted simple, generic hand, stick, knife and gun. But still, the background-depth, time and grade, experience is irreplaceable. Mike Gillette said once, “you are really paying Hock…for his eye.”

His eye? Eye? Look for a moment at my Australian friend Nick Hughes, currently in North Carolina, USA. Yeah, he teaches Krav Maga, and yeah, so does every Tom, Dick and Henrietta these

I often peruse the internet martial arts pages and I read stories of 25, 30 to 45 year old martialists and martial artists and their compulsion to publicly write – as one might in a personal journey or diary – about this or that small martial epiphany. Been there, done that, kid, and I quickly get impatient and bored with their tales which is my flaw, because I have to remember everyone is on their own splayed and fileted journey. Their mission, however on or off it might be.

What is your mission in this dharma-dilemma? Are you…”martial-mature?” How’s your “eye?” Look, I want people to be happy. Do what makes you happy, sports, art, combatives. Mixed? Mixed-up? Fun? Comradery? Whatever. People even like all kinds of mixed-up, martial arts to fool around with! Just know where it all fits in a big picture. Your big picture.

The teacher’s curse, “Survival? Or addictive hobby?” “In the martial arts world – There is so, so much to do and so, so much of it is addictive, but so much of all that addiction is extraneous, superfluous, abstract, distracting and unnecessary. Yet still this curse – the mandatory basics become boring, no matter how utterly important it is to utterly master them and them alone. It seems we will never stop wrestling with this fight against boredom. The “art” of the survival teacher is to find the best, reduce the abstract and somehow trick-hypnotize-engrain the student into doing it…first, foremost and forever.

You can use your mature eye to take the “mixed-up” out, and to leave “mix” in. You can take things from a martial art that has a high percentage of success and NOT take the whole damn system. Or not? Just don’t be…off-mission, off your personal mission. In the mixed up, forked roads of martial dharma – the “eyes” have it.

____________________________

Hock’s email is HockHochheim@ForceNecessary.com

A lot of American football coaches and players watch game films. I instead, have watched hours of football “how-to” training films to see how these players TRAIN. If you have ever spent time with me, you’ve heard me brag for years, decades even, on how American football training methods can be diced and altered to enhance, inspire and supply power-contact exercises for martial fighting. You’ve heard me say that a knife fight might not look like a movie duel, but might instead look like “football with a knife.” Same with sticks.

So, I take a hard look at football, hand drills-methods that enhance all that. The of quality football players, starting at college on up, is record breaking incredible now. These increases come from several methods, but two methods are clever drills and exercises for functionality.

One Quick Observation in and around on this subject. Australian football – or “Footy” is tough as hell, and like Rugby, sort of like soccer, are “chase-games” without the consistent line of scrimmage collision battles that can be reminiscent of, and can resemble a common collision in a fight, crime or war. Every football play starts with what a chiropractor might call, a small car crash.

Second Quick Observation in and around this subject. A fad move today is teaching an arm drag to get outside of an opponent’s arms and then pivot around them to get a rear bear hug. In demos and seminars, many “show-ers” just…just end right there with the rear bear hug. They show no more. Huh? They stop there, as if, with the bear hug it’s…over? Nope, it’s just getting started. Yet naïve rookie, seminar attendees (usually gun guys exploring unarmed combatives) think its manna from heaven. Some instructors will show a follow-up. They demo a bear-hug follow-up solution and they will lift up and body slam the opponent to the ground, of course falling with them too, to enter into the world of non-stop, one-dimensional wrestling. Such is their brain-washing. Usually both these demo people are 30ish-year-old athletes. But when we look around at ourselves, at each other, differing sizes, ages and strengths, is a 150 to 250 pound body lift and body slam of the enemy practical for the masses? Hell no. I can’t pick up, least of all, body slam a 175 or 200 pound person! And anyway, I want to remain up as much as possible.

A Third Quick Observation in and around this subject. American football obviously deals with face-to-face, frontal to frontal tackles, and not always chase tackles. They also cover power drills with pads to counter tackles, done in clever ways that any citizen should try and would enhance the subject, beyond typical martial arts classes.

In Summary, The Problem Is, His Arms! They are almost always are in the way. And they have muscles and seem to have a “mind of their own!” Here is a fast, short list of some football training drills I have collected on trapping and the “Football-Hand-Fight.” I can’t put videos in a book so I have to share them here. They incorporate Stop 3 Forearm Collision materials, and Stop 4 Shoulder Line collisions. Would you watch them for training ideas, adaptations, and inspirations?

For more diverse training…

Binge and Purge – The Martial Arts – Or, How I Learned Not to Need Subsection 3B of the Ukulele Islands Miasma Fighting System

I was watching medical doctors discussing things in a lecture and one said, “Remember back in med school? They told us that 50% of what we are learning will be disproved in ten years.” The board of doctors all nodded. 50% is a lot. In a way, in all fields, the sands can shift under your feet too. Psychology, medicine, science, athletic performance. Fighting. Acne removal. Shoe polishing…prepare to be wrong.

There is a usual amount of talk about the evolution of the martial arts through the centuries and in recent years. The islands of Hawaii were a filtering point for many martial methods as they passed from Asia to the USA. Bruce Lee publicized the barrier-breaking ideas of Jeet Kune Do. MMA (with ground n pound) has evolved to maximize success in sports fights. MMA fights are great laboratories.

I am known for confessing that I am not in love with martial arts per say, nor am I addicted to any one, two or more of them. Per say. I seem to have other odd motivations. These motives have somehow caused me to travel and teach. People say to me,

“It must be great to travel around and do what you love.”

Well, I…I don’t love this. No. Teaching is just a job. A job I got in and evolved in a very odd way from my…my odd “disorders.” Basically, I learned a lot of stuff. Then people learned that I learned a lot of stuff. As a result, people wanted to learn what I learned. I slowly started teaching on the road in the 1990s. Things slowly grew.

Why did I learn a lot of stuff? What motives? I have a very odd, sickness or obsession about tactics, since I was a kid. I don’t care where it comes from, but rather how valuable they are. I am not a historian, pigeon-holing methods into period pieces. If I know that history stuff, it’s just by accident. I suffer from a neurosis that has no name? Martial Syndrome? Martialitis?

I am not a copy machine, replicator of old stuff for the sake of hero- worship, or system-worship. I want to evolve or even de-evolve if need be. So, like the doctors mentioned above that some things are fixable/replaceable? Smarter, better? Replace it. Since I don’t care about martial arts…per say…I don’t really care about collecting a dead (or living) guy’s subsections of subsections.

After years in “Kuratey-jujitsu” since 1972 and military and police tactics, some sort of sickness then switched on in my head way back in 1986 when I saw the Inosanto/Bruce Lee approach. I can honestly say that not a single day since 1986 has my mind not thought about, or wandered to, some kind of martial subject. Obsessive thoughts. Pervasive thoughts. It’s unhealthy. I don’t know why. I could collect baseball cards or stamps or bowl like the Dude Lebowski. Instead I collect…hand, stick, knife, gun tactics. Are there any drugs for this malady?

And in pursuit of this collection, I have a peculiar paranoia. Not a typical paranoia, like a fear of “the streets” and being “attacked.” Not a paranoia of what is lurking behind every corner. Not that kind. Not that those things don’t cross my mind, but rather I have a serious fear of…”missing something worthy.”

WHAT am I missing , I fear? Who is teaching what? What do they know that I don’t know? How far am I falling behind? What’s that move? That drill? After all these decades, I do understand that most martial things for me are redundant and repetitive, and there is a lot of repetitive bilge. But maybe not sometimes? When you suffer from this malady, the desire to collect and fear of missing something, you have to keep eating – and you can’t help yourself – but…but…eat and purge. Eat, eat, eat and then purge.

You know that bad news about eating/binging and purging. People can die! It rots your pipes! But many people don’t die. In the process they seem to retain enough vitamins/mineral/nutrients to stay alive!

New for the sake of new…is not new. This has been going on a long time for marketing and business. And the grass is always greener. People fall for the esoteric just because of mystique. In the USA, the new “pain rub” medicine must come from Australia. In Australia, it must come the USA. You need to have an educated eye to see through this manipulative crappola.

After these last forty-odd years of odd study, working with smart people, sparring with and without weapons, shooting sims, arresting hundreds of people and working assault, aggravated assault, rape, robbery, attempted murder and murder cases. I have an “eye.” While I am deficient in so many, many things and ways, and I cannot do many things, I do have an evolved eye for fighting things. I can dissect them. And now more than ever I see the vast number of tactics and techniques on all these video clips. I can instantly spot the esoteric, flashy unnecessary moves people do. And sadly I can see the salivating onlookers, so naively impressed. They often fall into cult-like hypnosis and hero worship over “new-that-ain’t-new,” or some fall into utter nonsense. Often what I see them do what they do, I can cut in half, even thirds, but what’s left ain’t sexy or cool.

(The…ahhh….sexy “Turban Defense,” as in over-wrapping your head, way too often because…because… ahhhh….well….)

I hope this sort of time and grade maturity reaches the salivating masses someday? But I also want everyone to be happy, to pursue their hobbies too. If you know you are addicted to the artsy esoterica? Then fine. Just know you are.

And so, my paranoia. My paranoia. Am I missing something? I will always be looking around, feeling inadequate. And I will go with you to see Miasma Swami Jo-Jo Lukahn teach his subsection 3-A and B from the Ukulele Islands. I’ll fool around with it a bit. Sure. But, I will most likely purge it later as redundant and unnecessary.

Binge. Question. Purge. Binge. Question. Purge.

+++++++++++++++++

Hock’s email is HockHochheim@ForceNecessary.com

Email Hock and get his free news-blast newsletter.